Man, my original plan was to go through the four issues of Uncle Scrooge that were issued as one-shots before it became it's own line--until I realized that, in fact, it was only three one-shot issues. "The Menehune Mystery" is the start of the line proper. In retrospect, it seems apparent that I was confusing Uncle Scrooge with John Stanley's Tubby. This is an unfortunate situation because it prevents me from making the brilliant observation that, of the four original stories, this is the only one that didn't receive a Ducktales adaptation. 'Cause it ain't true! Bah! Humbug, also.

Well, never mind. But here's the thing: at some point in the past, I'm pretty sure I've complained about the fact that people on inducks are seemingly incapable of distinguishing between Romano Scarpa's good stories and bad ones, which could lead the inexperienced reader to incorrect conclusions about his overall oeuvre. Of course, this is not much of a problem for Barks, inasmuch as he wrote very few stories which are not at least okay. BUT THE FACT REMAINS: as of this writing, "The Menehune Mystery" is rated the twenty-fifth best Disney story EVER on inducks. AND THE OTHER FACT REMAINS: it's a pretty darn shitty story. Sorry if I'm trampling all over anyone's sacred cows (there's a bizarre mixed metaphor), but any reading even partially unclouded by nostalgia reveals that it's one of the worst things Barks ever did. One of the reviews on inducks says: "When we were kids my cousins and brothers always selected this as the best of Uncle Scrooge stories in our solemn yearly Disney Comic Contest." This makes me seriously conflicted, because on the one hand I love the shit out of the fact that they had a solemn yearly Disney Comic Contest, but on the other…man, I think the panel of judges may not have been wholly competent to carry out their assigned duties.

The funny thing is, I didn't read this as a small fry, and when I DID read it for the first time, I thought it was pretty cool. We will get into the reasons for that and more a little bit hence, but the basic problem is quite simple. This is the second big ol' Scrooge vs. Beagles outing. In the first one…well, do I need to say any more about the first one? It was an epic battle in which Scrooge's abilities were tested to the very limits, he comes desperately close to total failure, and only wins out due to a terrific effort of will. Whereas in this one, he is totally, consistently ineffective throughout but wins anyway because magic elves. Well, then.

The story makes a bad impression right from the start: this isn't the first time Scrooge has flat-out cheated his nephews (eg), but it's certainly the first time since Barks had put serious thought into what kind of a character he wanted Scrooge to be. Sure, the "earned it square" business is frequently more than a little flexible, but to see it flouted so blatantly, so early on--man, I just don't like it. It irks me, especially as it's totally unnecessary for the story that follows. If we wanted, we could make a sour comment in which we rhetorically ask how different this kind of willing slavery is, really, from the kind the Beagles eventually inflict on the ducks. That might be kind of interesting if the comparison were stressed in the story. But as it stands, it's just something I made up, and it's not really very interesting at all.

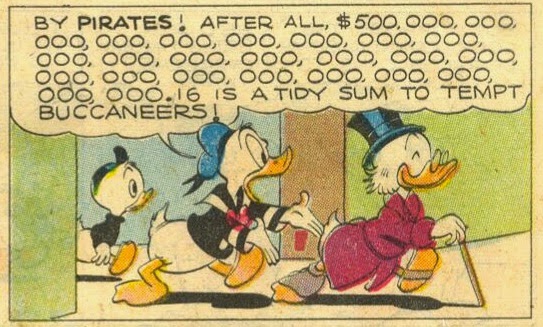

If you're counting, that's five hundred quattuorvigintillion, if we trust the nomenclature here. That's a mouthful. The recurring sixteen cents are kind of interesting--someone should write a meta-ish story explaining that, if they haven't already.

Is Scrooge really suggesting that the penalty for opening one of his spinach cans is death? This whole story just has something slightly off about it. That bottom right panel is pretty funny, though.

And there's all this absolutely interminable shit about Scrooge's shipping plan and the robots actually being Beagles and blahdy fuckin' blah. One can perhaps discern the embryonic traces of later, better, "Scrooge transports his money" stories, but what we get here just isn't interesting.

…particularly because they make all these clever plans, and they all turn out to be completely useless. There's no point to any of them. It's just making time.

So our heroes spend most of the story as slaves, until they're saved by a helpful deus ex machina. The thing is, though, there is a certain appeal to this, which is why I liked it the first time I read it. It's so shocking to see them so reduced, you can't help but identify and think MY GOSH THIS IS AWFUL WHAT WILL THEY DO?!?!? As emotional appeals go, it's not very sophisticated, but it's effective in it's own crude way. It's why I liked it when I first read it--and the appeal obscured the large and obvious problems with the story. On rereading it, however, I couldn't help but bring my critical faculties to bear--which does not do it any favors.

…and the thing is, I think it actually couldwork. It's surely interesting to see a situation in which, in contravention of the normal conventions, our heroes are suddenly denied all agency. But the story never goes anywhere interesting beyond the bare premise (it ain't exactly Twelve Years a Slave, is it?), and I really, really think it's important for them to regain some measure of control at some point. It never happens, though.

I mean, a story where our heroes are imprisoned and then rescued by good faeries is essentially a faerie tale. Only in a faerie tale, the protagonists would be saved because they helped the faeries or otherwise did something to demonstrate their exceptional virtue. But that isn't the case here. The ducks are only the good guys by default. Of course, when it comes to real-world slavery, that doesn't matter--monstrous evils must be remedied. But here, given the kind of story this is, that really doesn't work. There has to be a positive reason to like them beyond the tautological "we like them because they're the heroes."

There are three escape attempts: 1) Scrooge tries to climb the mountain but gets caught in shrubbery; 2) Scrooge and Donald try to climb it but get sick from eating too much fruit; and C) they climb it but don't have a match.

These efforts are all just so bizarrely hapless. it seems really, really obvious that Barks was totally on autopilot here.

…oh, and also, stuff with HDL trying to catch fish, which also seems incredibly pointless, save that it provides the opportunity for exposition, making the eventual menehune revelation marginally less weird. The structure here is incredibly questionable at best.

Pretty flowers, though. If nothing else--and there's really precious close to nothing else--"The Menehune Mystery" sure does look good. As you may know, this story was written around the time that Barks married one Margaret Wynnfred Williams, and the idea for it was suggested by the future Garé Barks, who had grown up in Hawaii. Probably one should avoid this sort of two-bit psychologizing, but it's just way too tempting here: it's common for creative people with unhappy personal lives to channel all their energy into their work; hence, you get stuff like "The Golden Helmet." But then--when they're happy, and don't need an outlet--you get stuff like "The Menehune Mystery." Does this theory hold up? Probably not--if it did, we'd have to assume that Barks was miserable throughout most of his career--but it seems plausible that a rush of new love could've led him to take his foot off the gas a li'l with this one story. Hell, if we wanted to really push it, we could suggest that the whole thing is a metaphor for how he was feeling about his life: buffeted around and abused by forces outside his control until--miraculously!--he's saved by what seems almost like a supernatural power. A religious experience for the devoutly areligious Carl Barks. Well hell, it's romantic, anyway, even if it doesn't do much to excuse the story.

I mean my gosh, even at the end here, when it seems like Scrooge could actually be taking charge a little bit--he doesn't. He still needs to be rescued by Hawaiian spirits. Bah.

However, to end on a positive note, I want to quote Geoffrey Blum (from the intro to this album, which does not appear to be indexed):

"Hawaiian Holiday" [Gladstone's alternate name for the story] suggests a more leisurely gestation [than Barks' usual MO]: it unfolds like one of Garé's landscape paintings, panning around the island, blocking in details of tropic fruit, fish, and foliage, and adding the fine brush strokes that bring everything to life: the hints of local color, the smattering of Hawaiian phrase, and the final gentle revelation of the menehunes. . . . His preceding Scrooge tale was a cutthroat treasure hunt on the high seas; his next would be an excursion to Atlantis. "Hideaway," like Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, is an interlude between two storm works: a sort of Hawaiian vacation.

I really appreciate this take, because I think it's valid, and it's an eloquent, charitable defense of the story--and, indeed, why not try to see the best in it? It certainly tracks with what I wrote above about Barks' possible psychological state around the time of his marriage. It doesn't change my overall opinion--I still think the story fatally flawed in terms of structure and character and more or less everything--but it provides me with a useful alternative hermeneutic, by which I can sorta kinda half-appreciate it nonetheless.

.jpg)